Princeville, North Carolina

Princeville, North Carolina | |

|---|---|

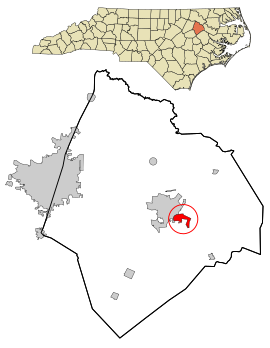

Location in Edgecombe County and the state of North Carolina. | |

| Coordinates: 35°53′18″N 77°31′44″W / 35.88833°N 77.52889°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | North Carolina |

| County | Edgecombe |

| Founded | 1865[1] |

| Incorporated | 1885[1] |

| Named for | Turner Prince[1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.52 sq mi (3.94 km2) |

| • Land | 1.51 sq mi (3.91 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.03 km2) |

| Elevation | 36 ft (11 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 1,254 |

| • Density | 830.46/sq mi (320.65/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 27886 |

| Area code | 252 |

| FIPS code | 37-53840[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2407162[3] |

| Website | townofprinceville |

Princeville is a town in Edgecombe County, North Carolina, United States established by freed slaves after the Civil War. It was established in 1865 and known as Freedom Hill.[5] It was incorporated in 1885 as Princeville, the first independently governed African American community chartered in the United States.

Princeville is part of the Rocky Mount, North Carolina Metropolitan Statistical Area. As of the 2020 census, the town population was 1,254 residents.[6] The town is on the opposite bank of the Tar River from Tarboro. The city of Rocky Mount is 16 miles (26 km) to the west.

History

As the American Civil War reached its conclusion, formerly enslaved African Americans sought refuge at a temporary Union encampment south of Tarboro, North Carolina along the Tar River.[7] With the assistance of the Freedmen's Bureau, these inhabitants developed their own makeshift settlement at the site and chose the name Freedom Hill in recognition of a small raised area where a Union soldier first announced the Emancipation Proclamation.[8][9] The land on which they stayed was owned by two white planters, John Lloyd and Lafayette Dancy.[10] There is no evidence that the two ever attempted to remove the freedmen from their properties, probably owing to the initial presence of federal troops and the poor quality of the land, which frequently flooded.[9] The community suffered heavily from poverty during its early years, receiving limited federal aid until the Freedmen's Bureau withdrew from North Carolina in 1869.[11] During the Reconstruction era, inheritors of Lloyd's parcel sold their property to planter Henry W. Shaw. Shaw began selling plots to the freedmen for low prices, though some residents continued to live as squatters. Black holdings grew near the Tar River bridge and more homes were built.[12]

Unlike most freedmen's towns in the Southern United States and in spite of its location in an agricultural region, Freedom Hill developed as a community with a workforce dominated by nonagricultural labor. The 1880 U.S. census recorded 379 inhabitants of whom only 12 were farmers and 43 were farmhands, with the remainder working in various trades including day laboring, laundering, seamstressing, carpentry, and blacksmithing. By that point community had also several white residents, most of whom were sharecroppers. Little is known about the white population of the town, though evidence indicates whites and blacks lived in separate areas.[13] In 1883 a school was established in the community. Several churches were also established, though available dates on their creation are not exact.[14] Local black residents were also, like their black contemporaries elsewhere in the state, politically active throughout the remainder of the 19th century, with local Robert S. Taylor serving as an Edgecombe County justice of the peace and William P. Mabson serving as a state legislator.[15]

Gradually both local blacks and the white population in Edgecombe County came to support the notion of incorporating the community. The black residents of Freedom Hill sought the advantages of local political involvement and self-governance, while whites in the county preferred having blacks available nearby as a labor force but socially segregated from their communities.[16] After several petitions from Edgecombe County residents, in February 1885 the North Carolina General Assembly incorporated the community as the town of Princeville, named in honor of local carpenter Turner Prince. The incorporating act provided for the town to elect its own government and scheduled their election in May 1886.[17] In the years following incorporation the town experienced increased commercial development as more locals established their own businesses.[18] Most of the town's political leaders emerged from the mercantile class.[19]

Princeville faced challenges throughout the Jim Crow era.[8] In the opening years of the 20th century, white business owners launched unsuccessful attempts to either dissolve or seize control of the town. By the end of World War I, more than half of the town's inhabitants moved to northern cities as part of the Great Migration seeking economic opportunities and an escape from white supremacy.[20] In 1967 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built a levee in the town to protect it from flooding.[21] In February 1997 the North Carolina Local Government Commission assumed control over the town's finances, the first time it had ever taken over the finances of a municipality.[22]

The town also suffered continuing difficulties due to its low elevation and adjacency to the Tar River. Princeville experienced severe flooding in September 1999 when Cape Verde-type Hurricane Floyd pulled coffins from the cemetery and raised water levels to just below the height of rooftops and church steeples.[23] The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency offered to buy out all residences in the town, but municipal officials rejected the offer.[21] In October 2016, Category 5 Atlantic Hurricane Matthew struck the town with similarly devastating results leaving residents with a decision between rebuilding and moving elsewhere.[24] As the town's population declined in wake of the natural disasters, its tax base shrunk and the county government assumed various responsibilities from the municipality, including authority over tax collection, policing, and water and sewer services.[21] In 2020, the Army Corps of Engineers announced $39.6 million in funding for a levee project to protect Princeville from future storms.[25]

Tourism

As the first town chartered by blacks in the United States, Princeville is home to several locations of historical interest. In 1999, students from North Carolina State University created a mobile museum for exhibits showcasing the town's unique heritage.[26][27] Historic buildings include the Abraham Wooten House,[28] the Mount Zion Primitive Baptist Church,[29] and the Princeville School, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2001.[30]

Financial difficulties

In a rare move, the State Treasurer's Office took control of the books for financially strapped Princeville in 1997 and July 2012.[31] In September 2021, a comprehensive town plan was adopted with emphases on resiliency, self-sufficiency, and economic growth.[32]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 1.53 square miles (3.95 km2), of which 1.51 square miles (3.92 km2) is land and 0.01 square miles (0.03 km2), or 0.69%, is water.[33]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 428 | — | |

| 1900 | 552 | 29.0% | |

| 1910 | 627 | 13.6% | |

| 1920 | 562 | −10.4% | |

| 1930 | 614 | 9.3% | |

| 1940 | 818 | 33.2% | |

| 1950 | 919 | 12.3% | |

| 1960 | 797 | −13.3% | |

| 1970 | 654 | −17.9% | |

| 1980 | 1,508 | 130.6% | |

| 1990 | 1,652 | 9.5% | |

| 2000 | 940 | −43.1% | |

| 2010 | 2,082 | 121.5% | |

| 2020 | 1,254 | −39.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[34] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 37 | 2.95% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 1,162 | 92.66% |

| Asian | 1 | 0.08% |

| Other/Mixed | 36 | 2.87% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 18 | 1.44% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 1,254 people, 789 households, and 556 families residing in the town.

2000 census

The 2000 census data reflect the town shortly after 1999's Hurricane Floyd; a 2004 census recount had been conducted, doubling the town's reported population (see above).

As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 940 people, 346 households, and 255 families residing in the town. The population density was 590.5 inhabitants per square mile (228.0/km2). There were 761 housing units at an average density of 478.0 per square mile (184.6/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 97.45% African American, 2.23% White, 0.11% Asian, and 0.21% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.64% of the population.

There were 346 households, out of which 27.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.5% were married couples living together, 27.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.3% were non-families. 24.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.72 and the average family size was 3.21.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 25.9% under the age of 18, 8.6% from 18 to 24, 24.9% from 25 to 44, 29.9% from 45 to 64, and 10.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 81.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 76.9 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $31,667, and the median income for a family was $35,625. Males had a median income of $23,281 versus $19,886 for females. The per capita income for the town was $12,603. About 14.0% of families and 17.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 30.9% of those under age 18 and 20.7% of those age 65 or over.

References

- ^ a b c "North Carolina Gazetteer". Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Princeville, North Carolina

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Freedom Hill Historical Marker".

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ^ Hill, Michael (2006). "Princeville". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ a b "Marker: Historic Princeville: From slavery to Freedom Hill". digital.ncdcr.gov. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ^ a b Mobley 1986, p. 342.

- ^ Mobley 1986, p. 341.

- ^ Mobley 1986, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Mobley 1986, p. 343.

- ^ Mobley 1986, pp. 343–344.

- ^ Mobley 1986, p. 346.

- ^ Mobley 1986, pp. 347–349.

- ^ Mobley 1986, pp. 350–351, 353.

- ^ Mobley 1986, p. 353.

- ^ Mobley 1986, pp. 354–355.

- ^ Mobley 1986, p. 356.

- ^ Mobley 1986.

- ^ a b c Flavelle, Christopher; Belleme, Mike (September 2, 2021). "Climate Change Is Bankrupting America's Small Towns". The New York Times.

- ^ "State Briefs : State takes over town's finances". Morning Star. February 5, 1997. p. 5B.

- ^ Pressley, Sue Anne (October 3, 1999). "Princeville, N.C., Settled by Freed Slaves in 1865, Faces a New Struggle for Survival After Hurricane Floyd". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ^ Black History and Floods Intertwine NYTimes, December 9, 2016

- ^ WRAL (January 9, 2020). "Princeville to get $39.6 million for levee project". WRAL.com. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ^ "Princeville Mobile History Museum". COASTAL DYNAMICS DESIGN LAB. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ^ Graham, Latria (October 27, 2020). "The Museum That Tells Princeville's Story". Our State. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ^ Hub, Macy Meyer UNC Media. "Princeville's history in good hands with Kelsi Dew". Reflector. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ^ "Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina". docsouth.unc.edu. March 19, 2010. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "With Princeville a pauper, state takes over town's books". WRAL. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ "Princeville Town Plan". Princeville Town Plan. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Princeville town, North Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved March 8, 2016.[dead link]

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

Works cited

- Mobley, Joe A. (July 1986). "In the Shadow of White Society: Princeville, a Black Town in North Carolina, 1865-1915". The North Carolina Historical Review. 63 (3): 340–384. JSTOR 23518785 – via JSTOR.